The History of UK Counter-Strike Esports

Reece Barrett, Senior Editor

Last Updated: 17/06/2025

Ad

In this special series of in-depth articles, Esports News UK, in collaboration with the betting partner GGBET UK, delves into the stories, moments, and personalities that have left a lasting impression on the past, present, and future of the UK esports scene.

In this article, Reece Barrett walks through 25 years’ worth of UK Counter-Strike history, covering trophy lifts against all odds, the breathtaking Birmingham Salvo win, the shifting UK CS scene at Global Offensive’s launch, and lots more.

Cast your mind back 24 years, when low-rise jeans were in, Y2K spared humanity and the globe ushered in the beginning of the new millennium.

England crashed out of Euro 2000 in the group stage, and while the football world was reeling with hurt, an iconic game was about to launch that would shape the future of competitive gaming.

A year earlier in British Columbia, Canada, two university students had developed one of their old Quake mods into something on the Half-Life engine that took the world by storm.

Minh “Gooseman” Le and Jess Cliffe were offered jobs at Valve in 2000, and spent the year putting the finishing touches on the first non-beta version of Counter-Strike, which officially dropped in September.

Critics were delighted by the game’s innovations, as the game brought the idea of buying guns and one-life-per-round to the mainstream masses for the first time.

North America was infatuated by Counter-Strike, and naturally, the fever soon swept across the Atlantic Ocean too – kickstarting a rich tapestry of history that still continues to be weaved half a century later.

The Early Days of Playing on LAN

Counter-Strike has been so much of a stalwart that to explain its history, you almost have to explain the history of UK multiplayer gaming itself.

In 1995, long-standing BT Group employee and avid gamer Colin Duffy had an idea that would get users to use their phone lines for longer.

He pitched a dedicated PC service that made it possible for gamers to dial into a server and play against other users, completely separate from their web connection.

BT would brand this service ‘Wireplay’ and rolled it out in June 1996 – the launch coinciding with the UEFA Euro 1996 event being held in London.

England started strong, but it’s England, and they fell apart in the semi-finals after a promising opening to the tournament.

Wireplay’s life span would play out in a similar way.

By 2001, the service had been sold off twice, passed around by firms and essentially became a shell of itself.

But two years earlier in 1999, Wireplay had 50,000 active users per month, and they looked to capitalise on their good image.

Enter Multiplay, a gaming events organiser, who teamed up with Wireplay to hold the first Insomnia LAN – a landmark opening ceremony for a LAN series that would go on to define the period.

The two brands teamed up to hold Insomnia 99, a 55 hour LAN party held in Bicester, Oxfordshire in March, which welcomed nearly 300 people after only originally advertising 250 spaces.

Coverage from the event hit BBC One’s National Breakfast News, and Multiplay would split from Wireplay after the first event.

Subsequent LAN parties would be known as the “i-Series,” with i2 hosting 229 gamers shortly afterwards in November 1999.

Their third event saw players take over a venue at Swindon Town FC, and Multiplay would host several events per year from 2000 onwards, eventually settling at a regular venue at Newbury Racecourse.

“The spiritual home of gaming has always been Newbury Racecourse for me,” said Tom ‘Gumpster’ Gumbleton, who has been Esports Director at epic.LAN since 2013. “Whereas I think people who have come into esports over the last five years would probably say the spiritual home is now Kettering Conference Centre.

“We’ve all grown up and come through esports and gaming differently. I come from a different time where we all just played for fun, like on LANs like these, but nowadays people are playing for stupid amounts of money.”

Wireplay’s dial-up service was strong for the time, but nothing compared to the experience of playing on a Local Arena Network.

Alex ‘AlesKi’ Way, who played for Team Dignitas’ main team between 2007 and 2008, said competing on LAN was “essential” to building a player’s skill set.

AlesKi said: “Playing at a LAN is a completely different dynamic and playing on a stage, even more so. For the early versions of counter-strike being on 5 ping rather than 40 made a huge difference to how the game played.”

While i-Series was keeping players entertained offline, moves were being made on online forums.

And before we had esports organisations, back then we had clans, groups of players formed to make competitive gaming teams. Counter-Strike clan ‘B!TCH’ floated the idea of a merger with a well-known Quake team in November 2000.

They would retain this Quake team’s name, crowning this new super-clan with the name ‘4Kings.’

Clan leader Jonny ‘TheGenius’ Neffgen had plenty of players ready to represent the brand, and a 17-year-old Marc ‘Mangiacapra’ Mangiacapra – who was using the name ‘Liquid’ at the time – stepped up to the main roster.

4Kings were in full swing by the time that London got an early competition in 2001.

CPL London 2001

International Counter-Strike LANs were certainly few and far between pre-2001.

4Kings had travelled abroad to Paris once for the ‘LAN Arena 5’ event. This time though, they would help welcome the world’s best teams to London.

The Cyberathlete Professional League (CPL) was founded by stockbroker Angel Munoz in June 1997.

As an American organisation, the CPL would host two tournaments per year to begin with, big BOYC LANs where teams competed for computer parts provided by sponsors rather than cash.

The brand grew rapidly in the USA, and while free-for-all deathmatch games were most popular to begin with, the CPL wanted to expand into Europe.

They set up a division to operate cross-continent.

There were teething issues with the first event in Denmark in 2000, but by August 2001, CPL Europe was up and running.

The Novotel Hammersmith was the venue of choice for this event, which boasted Quake 3 Arena and Counter-Strike tournaments with a combined prize pool of €30,000. There was also space for 300 gamers to unite in a BYOC area away from the competition.

In terms of teams for the CS event, Emil ‘HeatoN’ Christensen’s Ninjas in Pyjamas were in attendance, with a roster that also included the organisation’s founder Tommy ‘Potti’ Ingemarsson.

SK Gaming’s German roster played alongside their country comrades mTw.

Resident superteam 4Kings were of course involved too. Their roster consisted of leader TheGenius, Doug ‘Grim’ Wright, Dan ‘DaNfRaG’ Lucking, Pieter ‘Darth’ Bas Kwak and Mangiacapra.

All five of these players were competing in their first competitive international LAN. Perhaps this is why 4Kings did not go far in this tournament.

25 teams were split into eight groups of three, with the top two in each advancing to the knockout bracket.

4Kings scraped through in second but were then dumped out in the Round of 16 by CS Armageddon – another team that featured Brits ‘THEKev’ and ‘Marsh.’

Ninjas in Pyjamas would win the event and the €5,000 first place prize.

After their early exit, 4Kings underwent changes, cancelling their participation in CPL Berlin – the CPL’s first European CS-only tournament – which took place later in the same month.

The massive nature of their clan meant that they had a huge pool of players to pick from when going to events, but after London, 4Kings decided to pick a permanent five man line-up.

This was done to ensure that the same five people were practising together every evening, which would in theory allow the team to build more chemistry into their roster.

4Kings then went stateside in December to compete at CPL Winter 2001 – a tournament unofficially considered the first Counter-Strike major. 86 teams attended, including NiP, SK and a whole host of American teams as the event was played in Dallas.

4Kings won their first two games but were then sent to the lower bracket after being beaten convincingly by NiP. They were not long for the loser’s path either, as Norweigen team Massive Attack sent them back home.

These CPL LANs are where Brit Craig ‘onscreen’ Shannon – who now has 863,000 followers on Twitch – cut his teeth in competitive play.

4Kings finished 9th-12th and won $2,000 for their troubles. That was their last LAN of the year, but once home, they would compete online on competitive platforms that were beginning to take off…

Enemy Down Comes Up

In 2002, a passion project was born that shaped the UK CS scene.

Players ‘Spike’ and ‘Wormfood’ had the idea of creating a UK-only league in October 2000, and after finalising an impulse-blue design in 2001, they launched Enemy Down on January 1st 2002.

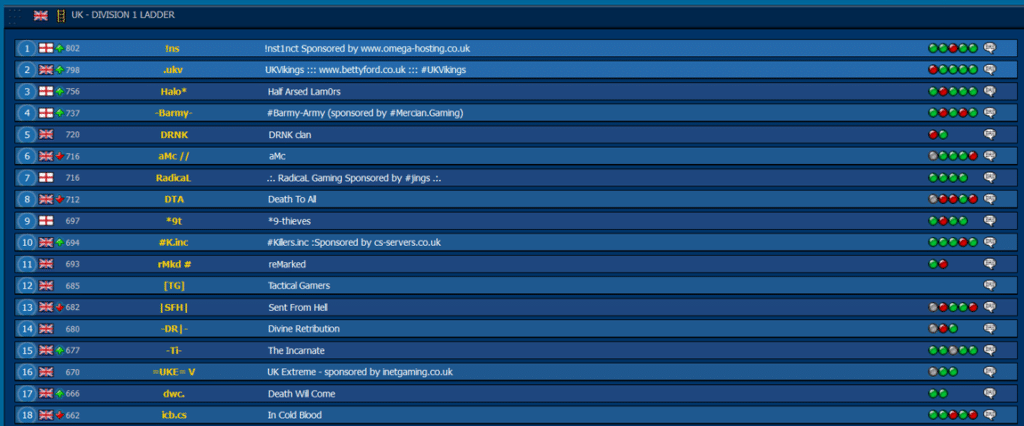

The website offered clans a platform to meet and arrange matches, with teams being split into three tiered ladders in the early days of the site – the ‘Premier’, ‘Standard’ and ‘HPB’ divisions.

“It was like a football league but you would schedule your own games,” recalled Tim ‘Cornish’ Kearse, who joined Enemy Down in January 2004 and worked as an admin until 2007. “So like football has the Premier League, Championship, League One and Two, the goal on Enemy Down was to go in at the lowest ladder, beat all the teams and get into the top.

“At the website’s peak, there was about 600 teams across four or five different ladders.”

If you beat a clan that was higher than you in your division, your clan’s score would be increased by a percentage of the difference between your scores – the higher the gap between the two teams, the higher the percentage.

If you lost against a clan below you, you would lose 25% of the points that they received for the win.

It was a somewhat confusing system, so the platform even had its own scoring calculator page for clans to use.

During the platform’s early years, teams would be promoted every five days.

Gumpster recalled how the site was fuelled by the love of the game, saying: “Occasionally there would be prizes for the ladders, but people mainly played it out of passion.”

It was entirely up to clans how they wanted to schedule their games.

Cornish said: “You could play four, five, six games in a night if you wanted to, and you’d put out a request to play a 5v5 MR12 or MR15 game.

“You could pick your own format and map so there was definitely some freedom.”

Even with this freedom though, you were not able to just get to the top of the ladder and then decline every challenge.

Teams were punished for being inactive, being docked 10% of their score after not playing a match for two weeks, and then being removed from the ladder altogether after a month.

“There was no agenda back then. It wasn’t about putting other people down or talking bad about other teams or anything, people just loved the game.”

Former Enemy Down admin Cornish speaking on CS in the early 2000s

Enemy Down was not the first website of its kind, as Clanbase had been similarly founded by gamers in 1998, but its unique selling point was that it was the main service that focused solely on UK clans.

Clanbase used the same ladder and promotion system, and also hosted regular tournaments, such as the EuroCup, which was open to clans, and the Nations Cup, which was open to single-nationality teams.

Chris ‘Meffus’ Goss, who was a starter for Team Wales and a stand-in for Team United Kingdom, gave more insight into how the leagues on both platforms worked.

Meffus said: “You were rewarded by being more active and trying to play teams above you. You could go straight into the big boys, and if you were at the top, you’d get tracked down because you were so far ahead of everyone else, and because beating you would get the other team known.”

The platform even infected the offline scene over the years too, with Gumpster remembering: “If you went to an i-Series LAN, Enemy Down would be on everyone’s screens. They’d be looking at the forums, because it was a congregation of the UK scene at that point, and if you weren’t on Enemy Down, you wouldn’t get noticed.”

Clanbase was well known for its EuroCup series that started in 2000, inviting the best teams on their platform to compete for $1,000 prize pools, which provided players with consistent paid tournaments in the early days of CS’ existence.

But while Enemy Down and its European competitor let players pick opponents, they did not hand out automatic servers like modern platforms such as Faceit now do.

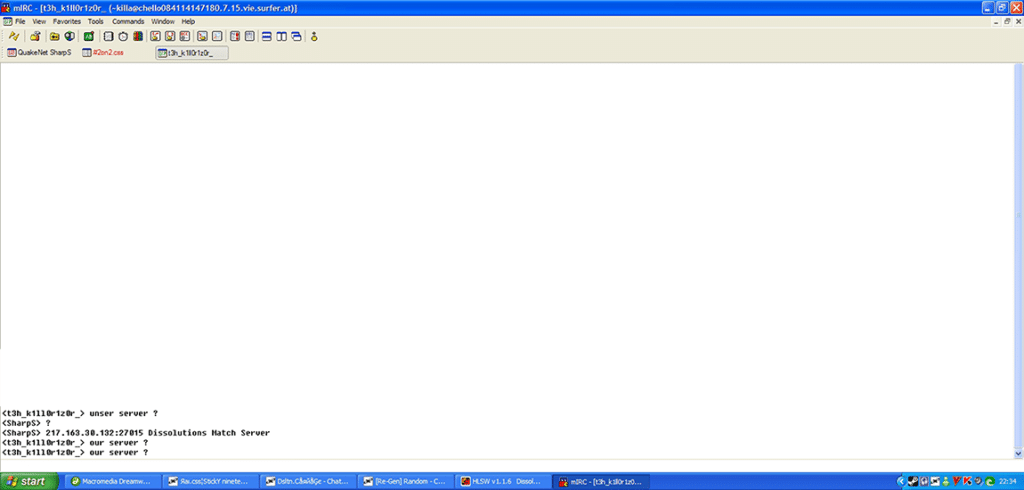

Clans had to pick a time to play, often chatting through external chat relay programs like mIRC, and for ranking matches this time would sometimes have to be approved by Enemy Down admins – volunteers helping the passion project.

“IRC clients were like a chat programme and you quickly learnt the channels you could use to search for games,” Meffus said.

“The real top echelon guys at the time were in their own private servers, so they knew they could go in, mix together and play against all the other top teams all the time.”

Former Dignitas, The Last Resort and TrademarkGamers player Rob ‘RobuLuS’ Dickin explained how the IRC landscape worked.

RobuLuS said: “You made a name for yourself by winning leagues online, doing well in LANs, and then you get invited to the invite-only practice ones with the best teams. I was in scrim channels with teams like SK Gaming, and since you had been invited in there, you had an idea that everyone in there was high level, you knew everyone was at least Tier 2.

“So you didn’t have to try find a game against a team of a random skill level and mess around with servers like you did in public channels, these teams were at a high enough level to be above that, and you knew because it’s invite only.”

While players were nothing like the stars they are today, the lack of coverage and livestreaming meant that sometimes it was hard to keep up with what was going on at the top level.

Youtube Philip ‘3kliksphilip’ Dyer did not ever play at a professional level, but found himself mesmerised by the early days of competitive play.

“The pro scene back then was, at least for me, shrouded in mystery. These days it’s shoved in your face, [on the] front screen of Counter-Strike, and everybody’s an expert on it. But for me I’d just look at teams at the top of Clanbase with the utmost respect, even if their entire history [only] comprised of six wins.”

Youtuber 3kliksphilip on falling in love with competitive play

Clan games were not broadcast like they are today. You would be lucky to find recordings of games on YouTube, and they would usually be from the POV of a player, not from a spectator cam. This was because all players had to record their own POV and submit their video to Enemy Down admins.

“A couple of years back,” former admin Cornish recounted, “I was moving house and loaded up my original gaming PC from 20 years ago.

“I was like, oh my God, I’ve got a 320 gigabyte hard drive full of demos, screenshots, IRC chats where people were talking about demos, I had just hundreds of hours of footage.”

Cornish did explain that you were able to watch games, but really you had to be there live to see it.

Cornish said: “We are blessed with Youtube now and that everything gets recorded.

“Back then, if you saw big matches going on, you would go on to Half-Life TV [Valve’s software that allowed unlimited spectators to watch online games, later becoming GOTV] and connect to it through your game.

“Some games had a couple of hundred viewers, but the bigger ones had a couple of thousand and as the internet developed, so did Twitch and other broadcasting which made [Half-Life TV] obsolete.”

If you need an admin on Faceit today, it takes just one click to call one in a match lobby.

But back in the Enemy Down days, you would have to rely on volunteer admins who regulated games as a passion project.

“If at the end of the match someone thought someone was cheating or something went wrong, you would submit a conflict which was flagged to us admins,” Cornish began to explain, his voice twinging with happiness as he rolled back the years.

“We’d download the match demo and request POV [recordings], and we’d sit there and manually watch specific points if they’ve been flagged, or sometimes even the whole game if it’s a continuous thing for a cheating accusation.

“You’d go through it, put your findings up, get a second opinion from another admin. I spent two hours every evening just going through demos after playing games, and it helped me learn more about the game because it was good to get an extent of understanding how others played the game.”

With Enemy Down and Clanbase not offering servers in the early days, some clans would try to push their luck by causing all sorts of mischief on IPs that they owned.

“Some clans had terrible servers,” 3kliksphilip recalled, “and there was a lot of hype about 66 tick!

“One Clanbase match we played, the other team was losing and did a weird server command that unbound all our controls, changed our name and caused us to float weirdly through the level until we disconnected and they scored the win.”

This was not so much of an issue on Enemy Down, and admins would obviously reverse scores on contaminated games anyway.

“There were no agenda back then,” Cornish explained. “There were barely any cheating accusations, such a small amount compared to today’s game. There was obviously some toxicity, but people just wanted to play the game.

“It wasn’t about putting other people down or talking bad about other teams or anything, people just loved the game.”

Enemy Down obviously had their problems with illegal software, but Meffus instead remembered more about the struggles of actually being able to play a game.

“I remember we’d sit there for hours and end up doing all sorts of different things while someone was popping in and out of chat channels seeing if any teams wanted to play and had a server we could use. It would be like three, four o clock in the morning and we’d have school the next day, but we were fully into the Counter-Strike vibe that night and we were just sat there waiting to find another group of people willing to play.”

Meffus on the true Enemy Down experience

Back then, platforms like Clanbase and Enemy Down were necessary because gamers did not have two Google pages worth of ‘team finder’ websites at their fingertips.

“You found people by visiting the same haunts over and over,” Meffus explained.

Players would go onto the same community servers every night and quickly make friends with the regulars.

“I had a group of friends in real life that got me into Counter-Strike, so I already had a few people to play with, but you just jumped into full swing on community servers and mingled with people,” Meffus continued.

“After you kept going onto the same servers, people got to know you, and that’s when I eventually got invited into a little community clan which was my first insight into playing Counter-Strike competitively.”

While the game has long moved on, and nobody can argue that unbinding all controls upholds competitive integrity, some do believe that modern CS has lost sight of its amateur roots.

“I feel the real ‘feel’ of Counter-Strike has been lost in a way? Valve have made it much easier to do all this stuff, they’ve made it into one of the biggest, most competitive games in the world, but I think it burns out the player base a lot faster.”

3kliksphilip on the current state of Counter-Strike

Meffus agreed that investment into the scene has made a once close-knit community feel artificial.

“I do think that you miss the rawness of it [these days] and how we had to make it work, the bonds we’ve formed through those experiences. But everything does sort of look a bit plastic and manufactured, and any industry is the same.

“You haven’t got bands who came up playing in their garages who became the Foo Fighters or Nirvana years later, and esports is the same in the sense that we’ve moved on. Money has been pumped into Counter-Strike and it’s much more accessible to your average individual, so [money coming into the esport] has been good in that way.”

Former admin Cornish also had a damning opinion on comparisons made between Faceit and his old platform.

“Faceit is phenomenal, but it’s all about the individual, and Enemy Down was about the team and the community. Everyone had the same goal of wanting to get to the top of the ladders and push their teams to the top, and Faceit right now is a great way for people to make the journey into esports, but it’s all about the individual,” Cornish said.

“There’s agendas now, and I don’t think the UK individual has the will to grind to it now. I played against f0rest in 1.6 and Source, and he’s made ridiculous money, but he’s spent well over 10,000 hours on the game.

“Why would an individual want to spend all that time to potentially not get picked up? There’s no clear end goal now on Faceit, not like it was back on Enemy Down, where the goal was to top the ladders.”

Regardless of how modern platforms has changed, Enemy Down formed the basis of competition and united the UK scene in the early days of CS.

But Valve’s powers that be made certain that a unifed competitive landscape would not last.

Source Splits The UK CS Scene

Two years into Enemy Down’s lifespan, Valve released a new version of Counter-Strike named Counter-Strike: Source (CS:S).

Le and Cliffe’s original mod was released on the GoldSrc engine, so this new edition was a complete remake built on the Source engine instead.

Development issues plagued the creation of the game, but Valve was determined not to release the game on Valve Time, so it was pumped out in October 2004 with help from Turtle Rock Studios.

But Turtle Rock had been working on another iteration of the game called Counter-Strike: Condition Zero (CS:CZ), which had only been released seven months earlier in March.

The behind-the-scenes of the CS scene seemed to be all over the place, and the release of two new titles threatened to split the community three ways.

But nobody cared about Condition Zero – Enemy Down did run a ladder for the ill-fated title but it didn’t see much competitive play elsewhere.

CS:S, on the other hand, immediately offered players nine graphically-overhauled maps with 3D skyboxes and slight layout tweaks.

At least, that is what it first seemed like, but as players got stuck in and dug deeper, they found gameplay niggles that were almost identical to those present in the early days of CS2.

“The difference between the games was huge,” AlesKi explained, getting technical with the mechanical differences between the titles. “Source had a completely different feel and demanded a different playstyle to 1.6.

“Peaker’s advantage in Source was huge compared to 1.6’s slower, methodical style, and Source rewarded raw aim and mechanics whereas 1.6 felt more tactical. They felt like entirely different games and these differences meant a very small number of players switched permanently.”

But much like how the transition between CS:Global Offensive and CS2 was jarring and jittery, the first release of CS:S was similarly sloppy.

“The other big barrier was it being so poorly optimised at first that a mid-range PC could barely hold 100 fps,” AlesKi continued. “[But] I think younger players started picking up Source over 1.6 as if you’d never played either you probably wouldn’t notice or care about these differences.”

Valve had tried to fix a game that was not broken, so those still interested in the tactically-sound 1.6 were not convinced to make the switch.

“[Source and 1.6] co-existed and ran parallel,” Meffus said. “You were either a 1.6 player and fan, or a Source player and fan, and you didn’t need to upset the apple cart by mixing the two realms, they just existed next to each other.”

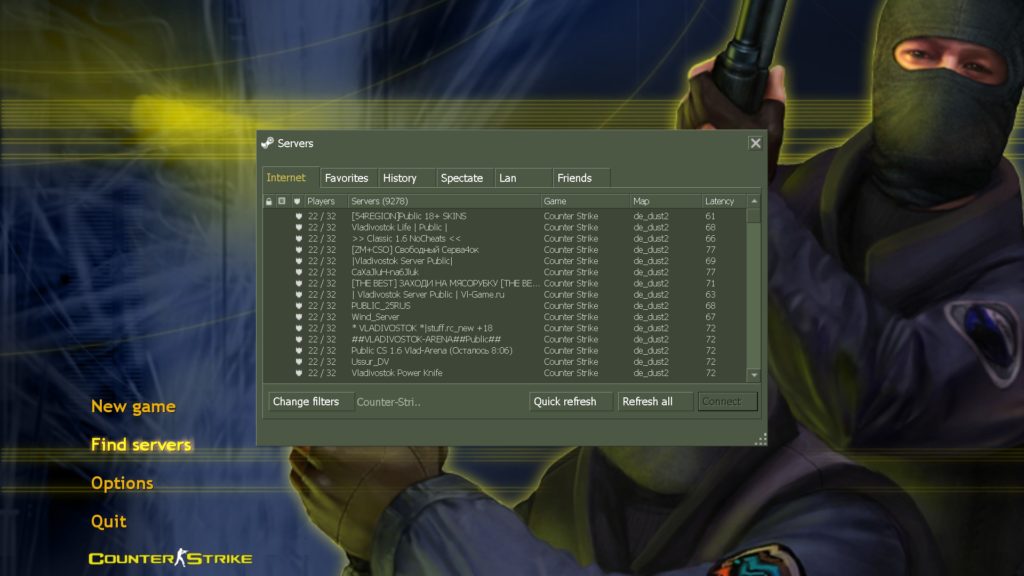

Players of CS:CZ quickly jumped to Source though, and Condition Zero has not aged well – for context at the time of writing there were only 164 available servers to join on CS:CZ while there were 9,278 still active on 1.6.

Counter-Strike 1.6’s elite talent would not move over to CS:S until 2008, when they took a pop at a golden goose called the Championship Gaming Series (CGS).

But we’re still in 2004 here, and while four years might not seem like a long time, we’ve got an awful lot to get through before we can get to the CGS.

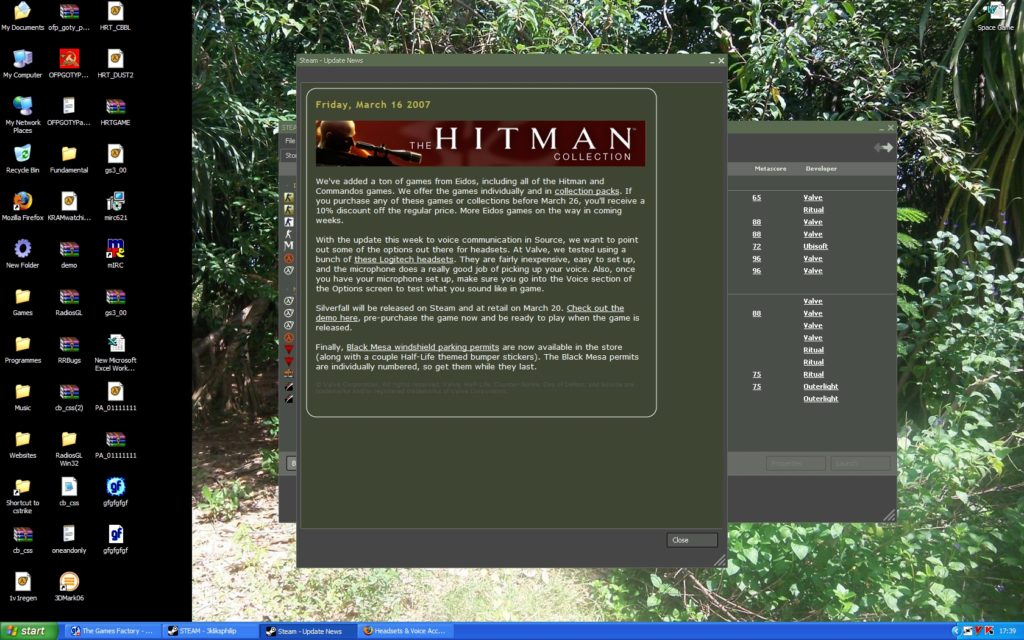

The launch of CS:S was also one of the big first tests for Steam, which had rather unsuccessfully launched a year prior in September 2003, around the same time Team Dignitas was set up in the UK by Michael ‘ODEE’ O’Dell (more on Dig later).

“Steam was horrible back then, and it kept crashing to the point where I renamed it to ‘S**t’ on my desktop,” said Vexxy, a Clanbase member. “Servers wouldn’t run well on it because the version of the backend system would never match the client version, so you constantly had to readjust your client version versus whatever the server was using.”

It would take a lot of work to develop Steam into the money-printer that it is today.

Team ZBoard Arrive

With CS:S released, the UK’s first ever Source LAN tournament took place in March 2005: i23.

A team considered “onliners” who had never played a LAN tournament arrived and would end up winning the event amongst allegations of bug abuse.

Regardless, this clan would win the event and their fair share of the £250 prize pool, claiming victory at 3am on Easter Sunday.

X043 – which stood for “extreme ownage” – was a roster that featured team leader Ben ‘ben0’ Balcombe and a 16-year-old Henry ‘HenryG’ Greer.

Scott “Toccs” Hawkins and ben0 had founded X043 in August 2004 on Condition Zero, but quickly jumped over to Source as soon as it was released.

After promising results early on, the team were sponsored by Ideazon’s ZBoard brand, which was one of North America’s most influential peripheral producers (later acquired by Steelseries in 2008).

Zboard decided to punt on the right horse, as after winning i23, the team went on to win the next two i-Series LANs – making them the first clan to ever win i-Series back-to-back-to-back.

They finished within the top three at i-Series events eight times.

Team Zboard started to become a very recognisable team for young players in the scene, but while they reigned as the number one team in the UK, some of their older players headed off to university.

It meant that the original line-up fell apart.

HenryG jumped ship to another team called Insert Coin, who Team ZBoard soon faced in a controversial qualifier match, where HenryG allegedly used an illegal defuse to eliminate ZBoard from the tournament, as explained here by British esports veteran journalist Richard Lewis.

Zboard needed replacements, so they looked towards up-and-coming talent.

“They started selecting young stars,” Meffus said, when talking about Team Zboard. “Most of the top gamers in the UK probably had a little stint in Zboard at one point.”

Competition was heating up, and down in Southampton, a new venue was catching local eyes, becoming the epicentre of the organisation that helped make esports what it is today.

Starbytes and The Birth of Fnatic

Sitting opposite Solent University on New Road in the city centre, Starbytes was an internet cafe that allowed users to pay a daily fee and play a whole host of games installed on their computers.

The idea of an internet cafe was not novel when they opened, but the organisation started building traction by hosting their own LAN tournaments on CS:S.

Chris ‘MGz’ Boggett was Starbytes manager between 2004 and 2009, and explained why teams wanted to play in the cafe’s tournaments.

“Because there was prize money, [Starbytes] had attracted teams from all over,” MGz explained. “Even Northern Darkness, which was Fifflaren’s team at the time.”

I'll finally admit that @Fifflaren beat me at the 2005 CS:S starbytes lan tournament. He played very well and I couldn't handle his team.

— HenryG (@HenryGcsgo) January 29, 2017

“We were in local newspapers and were written about by esports websites as far away as Asia.”

Starbytes hosted the country’s best, and often teams from abroad too, but MGz still remembers one underdog story clearly.

MGz recalled: “My favourite moment was when unknown team cs:punK went 6-0 up against Team Zboard. But I restarted the wrong server.

“I offered two options to them: restart or have $10,000 money at 6-0. [cs:PunK] said restart and lost 16-5.”

But as explained earlier, as the game developed, cheats did too, and MGz’s Starbytes was not immune to the epidemic. Some of this illegal software was distributed by players and figures who were still in the scene themselves.

MGz said: “[Software called] x22 was spread, there was also commands to get rid of smokes and to see physical objects through walls, anything that has physics could be seen, so not live bodies but guns could be seen so you’d see floating guns and the bomb.

“There were low FOV aim bots, vent.exe was spread, I saw [some members of] Team ZBoard chatting at i-Series and using the overview bug as well.

“I much prefer the integrity now and how it’s done. I was the George Best to Paul Gascoigne era. Rarely practice, no sports science. Now it’s a real sport taken seriously. [It’s] what I always wanted.”

And while not strictly Counter-Strike related, a young Sam ‘zr0’ Mathews would regularly come to play Painkiller while he studied at the University of Southampton.

“It was during one of these visits that he decided to create Fnatic,” MGz revealed. “It was called Impulse Gaming for a short while, but we convinced them to go with Fnatic. His uni mate Mac [Nicoll, Marketing Manager at Fnatic hired officially in November 2006] designed the logo, Sam sold his car and they sent ‘Vo0’ [Sander Kaasjager, Painkiller and Quake professional] to CPL Dallas.”

Fnatic officially announced Vo0 on July 23rd 2004.

On the same day, they revealed that they had also merged with Unreal Tournament squad “Xtreme,” Call of Duty team “Kreaturen” and female Counter-Strike side “m!ss undaZtood.”

The UK-headquartered Fnatic have always been huge supporters of female Counter-Strike, signing a ‘Fnatic Ladies’ side in March 2010.

It was not long before Vo0 was winning CPL events in Instanbul, Rio de Janeiro, Jönköping, Sheffield and Milan in 2005 – all of which were televised on MTV.

“We didn’t just dream that esports would blow up. We believed it would sooner or later.”

Starbytes manager MGz speaking about MTV’s involvement in esports, and how it showed promis

Later on in 2007, Starbytes would rent the top floor to Fnatic, and this became Fnatic’s first headquarters before they later moved to London, where they went on to play an essential role in building the esports industry into what it is today.

While Sam Mathews was starting a sports sedition in Southampton, two UK teams were reaching world-class status in Counter-Strike.

New Stars Rise

So now that we know where people played, and who they competed for, who were some of the rising stars making waves in the mid 2000s?

On the 1.6 side, a British-Nordic mixed roster at 4Kings were leading the charge.

Stuart ‘Harriman’ Harriman and Mangiacapra were standouts on that side throughout 2003, with the latter actually pausing his Computer Science degree in 2003 to continue to compete.

Mangiacapra had played badminton at a national level before being forced to stop due to an injury, so he was no stranger to competition.

He eventually left 4Kings and went inactive for a little while.

But the stars of 1.6 eventually started to come together in 2006, when Team Dignitas signed Goldbrick, a team led by the legendary Sam ‘RattlesnK’ Gawn.

This move was made in 2007, and as the months went by, RattlesnK chopped and changed players to find the perfect roster.

In January 2008, they made a triple transfer that introduced Elliot ‘wEZ’ Welsh, Peter ‘pt’ Wright and James ‘wilzOOO’ Wilson.

All were exciting moves, but wilzOOO in particular was known as a particularly helpful player in the scene.

Meffus said: “I remember wilzOOO gave some of the best advice I had ever heard, telling us that whenever you take a fight, never give the player more respect than they deserve. He believed that whenever you’re going to commit, you’ve got always commit knowing you’re getting the kill, because if you hesitate just for that nanosecond you’ll be dead.

“He had that confidence to play with freedom, to give teammates the freedom they need, and that freedom and confidence is the reason why someone like s1mple is so good.”

As the year continued, Harriman was brought into the team, and wilzOOO was replaced by a returning Mangiacapra, reuniting the long-term 4Kings teammates.

The scene knew that these changes were made for a reason, as Dignitas were bolstering their roster ahead of a landscape-changing event.

“[wilzOOO] had that confidence to play with freedom, to give teammates the freedom they need, and that freedom and confidence is the reason why someone like s1mple is so good.”

Meffus speaking on how wilzOOO gave some of the best advice

Elsewhere, 2006 marked the first UK representation at the ESWC Female events, as ‘HBee’, ‘Ms.X’ and ‘Jaffy’ played alongside an American and a Swede as girlz 0f destruction.

HBee and Jaffy would attend the following year too with UK players ‘vorny’ and ‘sugarism’, forming G-Stars.

By 2006, Enemy Down was beginning to be replaced by league platforms such as the SGL or CSGN.

“You had divisions, seasons, kind of like ESEA does today,” said RobuLuS, as he explained how the SGL and CSGN worked. “You played teams in your league on scheduled days every week and eventually had a winner, with the ‘invite’ league at the top as the main division.”

There were still fans of the ladder format however, especially across the border in the world of Source, where it was Reason Gaming who led the way, a long-running UK org led by Adam ‘Blanks’ Heath today (who took over in 2012).

We also narrowly missed out on one of the EMS One events in Colone by a single Bo3.

— Roger Paynter (@p4ynt) May 28, 2024

Lewis ‘Hughsy’ Hughes made a name for himself alongside Tom ‘url’ Chenery and Jonothan ‘Jon0o’ Finglass, the latter of which had previously won the Halo Worldwide Championship 2004 in Los Angeles. The fourth member of this team, and the in-game leader, was an 18-year-old HenryG.

After playing a key role in a Clanbase Nations Cup win with Team UK, HenryG left a clan called CSA and helped form this new Reason side.

The youngster was becoming very well-respected as an IGL after strong stints in teams, and this new group of Reason players would make a very strong team.

They bested Team ZBoard, who were still trying to challenge Reason, in the grand final of the 2007 StarBytes Winter Warmer.

The fifth and final member of Reason’s roster was Richard ‘ritch’ Gibbs, one of the UK’s best mechanical players ever.

“I met ritch on a random community server,” recalled Meffus.

“ritch was one of those guys who just picked up the game and managed to kill everyone instantly. People were kind of slagging him off because they thought he was cheating, and I ended up being amazed by this dude, texting him saying ‘you’re the best player I’ve ever come across’ and he was so polite to me.”

Meffus on ritch’s raw skill and their friendship

Enemy Down admin Cornish praised ritch’s mindset too.

Cornish said: “His passion for the game was brilliant, he wanted to win everything he possibly could. He had the drive to do it, and he did exactly that, and that drive is something that I think the UK lacks nowadays.”

While his ability was second to none, Cornish recalled that ritch used to rub people the wrong way and “often got banned” for being “very outspoken in his views”.

Meffus continued: “If you were nice to him, he’s like one of the nicest guys and friends you could meet. My daughter is in ritch’s will. I think people these days won’t realise the type of friends you could meet on community servers.”

Ritch did not just leave a lasting impact with the trophies he won, which we will come onto shortly, but he would also influence the next generation, inspiring one Dane in particular who would go on to become one of Counter-Strike’s greatest ever.

Cornish recalled an anecdote from a few years back, saying: “Me, Ritch and some others were playing Valorant, and dev1ce was playing on the other team.

“dev1ce goes ‘Ritch, is that really you?’ and he said that he used to look up to Ritch when he was growing up.”

Cornish remembering when four-time Major winner Nicolai ‘dev1ce’ Reedtz recognised ritch

“And what, 15, 20 years later, a superstar like dev1ce remembers him? Just from that conversation, I still think that Ritch was the best British CS:S player, and he clearly left quite an impact on someone who has gone on to do amazing things.”

This Reason Gaming roster was later acquired by 4Kings in May 2007.

While this team had been with Reason since 2006, HenryG said that the offer was too good to turn down in an interview with 4Kings upon the announcement.

“Reason Gaming is a great organisation and we had some great times there. But it never had the professional attitude that we desired. We want to prove to everyone that we are a world class team and to do that we need a world class organisation.”

HenryG speaking to four-kings.com upon leaving Reason Gaming to sign with 4Kings

With 4Kings acquiring their new roster and Dignitas freshly-changed on 1.6, there were now two elite-level teams in the UK, segregated and left to dominate on parallel paths on their respective games.

But as 2007 approached, an opportunity arrived on CS:S that was too good to turn down.

It was time for these titans to finally clash on a big stage, and it would take place on esports’ first major professional platform of its kind.

The UK CS Scene Storms the Championship Gaming Series as Birmingham Salvo Win Big

In 2005, former Fox Sports president David Hill took over at DirecTV, and quickly set about getting his claws into the esports industry.

Hill obtained $50m in funding from Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation and conceptualised a multi-game league that would sign players and teams to exclusive contracts, preventing them from competing in other tournaments.

The Championship Gaming Series (CGS) was announced in January 2007, and while Hill would abandon the project to return to Fox Sports in March, his idea lived on.

DirecTV partnered with BSkyB and Chinese network Star TV to finance the league and secured sponsorship from Alienware and Mountain Dew.

The funding was massive, allowing the CGS to pay players huge salaries, and this was especially important because earning a salary as a player at the time was unheard of.

“It was the first real inkling that this could be a viable career for people.”

Meffus, speaking on the inception of the Championship Gaming Series

“These guys were putting all this time and effort travelling around Europe, the UK, lugging their PCs with them on trains and stuff [to BYOC tournaments],” said Meffus. “Suddenly they could be earning a real, decent amount of money here.

“It was mind blowing for people, because with the money and the exposure, suddenly the mainstream media were picking it up and getting involved in gaming.”

The CGS featured franchises from across the world, with the European representatives being Berlin Allianz, Stockholm Magnetik, Birmingham Salvo and London Mint.

Salvo was led by Team Dignitas founder Michael ‘ODEE’ O’Dell who was the general manager for the side, and arguably the UK’s first pro gamer Sujoy Roy managed London Mint.

These franchises competed in Dead or Alive 4, Forza Motorsport 2, FIFA, and after careful deliberation, Counter-Strike Source.

These franchises competed in Dead or Alive 4, Forza Motorsport 2, FIFA, and after careful deliberation, Counter-Strike Source.

The choice to pick Source over 1.6 was one that changed the scene.

CGS promised huge salaries and exposure, plus the opportunity to live in a gaming house out in Los Angeles, so 1.6 players were not going to miss out on those opportunities.

Suddenly, RattlesnK’s Team Dignitas, who were only playing 1.6 at the time, were booting up CS:S.

“I don’t know if they would have played Source at all if it wasn’t for the CGS,” AlesKi said, weighing in on the players who jumped ship. It was the first [CS] tournament that had proper TV production, it was entertaining but the format was terrible for competition.”

AlesKi was right about the format. While the split scene was about to clash for the first time, the CGS decided to confuse everyone by using a completely different scoring system for their CS:S matches.

The traditional MR15 format was abandoned entirely, with teams playing two halves of nine rounds and ‘winning’ once they hit 10.

Except it wasn’t just a best-of-three like you see in Counter-Strike today, instead matches were decided by an aggregate score in a football-like manner, meaning that every round won across all maps counted towards the overall result.

Cornish scolded the altered format, saying: “It was action all the way through, and they were throwing around life-changing sums of money for people back then.

“It was all so American, changing the games to shorter rounds, and to me it was the first stages of the Americanisation of the product as a spectator sport, and that’s only kept on going as the internet got commercialised as a whole.”

While mainland Europe was innovating tactically, the CGS wanted to show off the gunplay, as players started off the shorter games with $9,000, throwing teams straight into gun rounds which might have actually benefited the British players.

“Firepower was what they thought spectators wanted to see,” explained Meffus. “So the UK did really well in the CGS because they had raw talent, mechanically gifted individuals who weren’t all aim no brain, but definitely had the aim.”

Players like ritch and RattlesnK just oozed confidence too, so by giving teams bucket loads of money only boosted the UK franchise’s belief.

Meffus continued: “There was a lot of ego with these [UK] players too, almost in the same way that you have top players like s1mple and donk who have no fear and truly believe that they’re going to win every duel.

“A lot of the UK lads felt that they were the best player on the server, that they were always going to take and win duels, so this [different] format for the CGS worked really well for that.”

With such huge broadcasting companies behind it, the CGS wanted nothing but the biggest names, and with their English franchises, they certainly secured local royalty.

A UK “combine” invited all comers to play in a tournament where franchise general managers would “draft” a team to represent them.

The combine was the first big tournament that Team Dignitas played on CS:Source.

Despite only finishing third at the combine, 4Kings were drafted by London Mint, while Birmingham Salvo general manager ODEE unsurprisingly picked his own Team Dignitas team.

Team ZBoard, led by ben0, had actually beaten 4Kings in the semi-finals, but they were left undrafted.

“ZBoard were the absolute favourites to make one of the franchise teams,” Gumpster remembered.

“I remember it being one of the biggest shocks of UK scene history, that this team, with all this history, did not manage to make it [to the CGS].”

Gumpster speaking on the CGS UK Combine, and how it was a shock that Team ZBoard did not get drafted

Despite the combine being billed as a way for teams to get their big break and salary, there was a feeling in the scene that decisions were made way before the event took place.

“The week before the combine, there was only two teams signed up,” MGz explained. “The pick[s] were kind of sewn up [before the combine], mostly due to [the drafted teams] being significantly ahead of the scene.

“The combine was rather general managers doing due diligence, [as if] it was a job interview. Winning meant winning, not being drafted.”

AlesKi reinforced this idea, saying: “Most of these players already had connections to a General Manager and knew way beforehand that they were getting drafted, like ODEE being the Salvo General Manager.

“It makes complete sense he would want players he knows and was comfortable with.”

The CGS tried to enforce exclusivity on their players but since the UK-based players wanted to play in local LANs in the off-season, they allowed “limited exclusivity” – franchises could play in other tournaments but must use their CGS team name and branding.

The entire league was heavily criticised in the years that followed its closure, but the involvement of Sky at least meant that Counter-Strike would be broadcast on national English television for the first time.

Birmingham Salvo did not disappoint in front of this new found Sky Two audience.

After reaching the semi-finals at the CGS World Championship 2007, ODEE’s team looked to build on the strong foundations they had laid.

While they smashed through the competition to win Insomnia 33 and 34 in the CGS off-season, changes would be made as the 2008 draft came around to give the UK franchises a chance to bring in new players.

These new team members did not have to play for another franchise too – they could be fresh signings from the independent scene.

HenryG’s London Mint brought in former Reason teammate ritch and ZBoard alumni George ‘hudzG’ Hoskins.

HudzG had actually had an audition of sorts at i32, as HudzG’s Reason Gaming (who had since signed a Nordic lineup) lost to London Mint in the final.

Salvo exchanged Harriman and AdY to gain wEZ and wilzOOO, and these transfers would prove to be perfect in the coming months.

But before the World Championship, Salvo first had to qualify through the European Finals.

Only the two top of the four teams at the event would make it to the main tournament, and RattlesnK’s side first beat London Mint to advance to the final, before beating Fifflaren’s Berlin Allianz to win the qualifier.

London Mint did win their third place decider match though, which took them to the Wild Card Finals – a three team event where the winner advanced to the World Championship.

The Mint were one win away from the $455,000 tournament but had their dreams shattered as San Francisco Optx knocked them out.

It left Salvo as the sole UK representative in the World Championship, and with the pressure of the Kingdom on their shoulders as they left for Santa Monica, they would not disappoint those waiting for them back home.

Heavy underdogs Mexico City Furia were Birmingham Salvo’s quarter final opponents, and while Furia actually won the second map, Salvo won on aggregate to advance to the semis.

RattlesnK spoke on broadcast after the game: “We went into the game thinking we were going to win easily, and that was probably our downfall.”

That famous UK ego was shining through again.

Salvo almost ate their words again as they struggled to beat Carolina Core, winning by just one round on aggregate as they battled their way into the grand final with a 21-20 win.

The former Dignitas then defied the odds to beat m0E’s San Fransisco Optx convincingly in the final 22-15, winning a landmark $500,000 in a final broadcast live on Sky Two.

“The biggest UK scene memory will always be RattlesnK winning the CGS,” Gumpster said. “I was watching that match late at night, stupid o’clock in the morning, seeing these boys win. It was a really great moment to witness, one of those ‘where were you on that night’ kind of things.”

Salvo’s victory was a proof of concept that the UK scene could dance with the deadliest in the CS world.

This triumph – broadcast to over 450 million viewers on national television channels worldwide – was not only one of UK CS’s best moments, but it also proved to young stars that there might just be something worth exploring in esports.

“I remember my Dad trying to tell me that there was nothing in gaming,” Meffus said. “Like most good parents, he told me to concentrate on school, that kind of thing.

“So then I tried to tell my dad that soon enough, people would pack out stadiums to go watch this, and he said it’ll never happen. And then I said nah, it will, because it’s on Sky now.”

Meffus on the CGS proving his Dad wrong and showing that esports can be a career

That backing from Sky was almost the self-assurance that people in the esports world needed to confirm that there could be a future in this.

The feeling was even more present outside of the CGS, as competitive platform Enemy Down were also celebrating success in 2007.

They had just hosted their Team Ebuyer tournament which gave the winning team the opportunity to travel Europe for events and play under the “Ebuyer” banner, representing the UK-based online tech retailer.

This competition saw 192 teams compete and had the largest UK prize pool for a Counter-Strike event ever at the time.

The success of a competition like this was also bound to attract attention. After the Ebuyer event, Enemy Down were acquired by The New World Assembly (TNWA) in July 2007 – a name which will quickly become important in our journey through CS history.

Team Dignitas continued to operate with a UK roster after their old team had been drafted by Birmingham Salvo. This iteration of Dignitas dominated the domestic scene in 2008 – mopping up spots to play at IEM III Dubai, the World Cyber Games 2008 and ESWC 2008 by smashing through regional qualifiers.

“The main reason we got to go to any international tournaments was the regional qualifiers,” said AlesKi, who played for Team Dignitas’ main team between 2007 and 2008. “It was standard back then for the prize to be an expenses paid trip to a finals somewhere. During 2008 we had a great run and managed to win nearly all of them and get some good experience playing against top teams.”

Dignitas tied against zonic’s mTw at IEM Dubai, and while they did not go on any big runs at any of the tournaments mentioned above, they were the main representation for the UK scene throughout 2008.

Salvo had smashed through the CGS, and the scene as a whole was keeping up with the rest of the world.

But while the UK were riding the crest of a wave, they would soon be brought crashing back down to Earth.

Economic Crash Causes UK CS Scene to ‘Evaporate’

The late 2000s brought the worst financial meltdown since the Great Depression as the world felt the effects of a recession.

Originally, the video game industry looked “recession-proof” as the sales of consoles continued to trend normally throughout the crisis. But the esports sector would not be so lucky. So many of the big tournament organisers disappeared almost overnight.

Clanbase owners GGL failed to deliver prize money for their EuroCup held in 2007 and the company would eventually go under in 2013 still owing €24,000 to tournament participants.

The CPL, which had supported Counter-Strike since the turn of the millennium, ceased operations in March 2008, citing “the current economic climate” as the reason behind their closure.

Other tournament providers were on the chopping block too, as The World Series of Video Games cancelled events in Los Angeles, London and Sweden in 2007 to shut down their business.

Wireplay also switched off the lights for the final time in 2014 after being almost-extinct since 2001.

But the biggest blow to the first ideas of esports as a career would come when the CGS announced its closure in November 2008 after two seasons of competitive play.

CGS representative Jenny Snegaroff said in a statement that “profitability was too far in the future to sustain operations in the interim,” and suddenly salaried players were made unemployed.

“The two biggest teams in the UK at that point, Mint and Salvo, were massively salaried. So all of a sudden these players have gone back to reality, and it all sort of culminated with a lot of big players retiring and a lot of communities disappearing.”

Gumpster explaining the financial implications that the collapse of the CGS had on the rest of the scene

After leaving Salvo after the 2007 season, Harriman went inactive and remained retired apart from a couple stand-in appearances in Global Offensive. Mint’s url also gave up competitive CS after the CGS collapsed.

Meffus said: “The UK went and gave a really good account of itself, and then suddenly it was over. I think some people saw that as the opportunity for gaming to really get pushed into the next level, and it didn’t happen, so they thought that was the end of that.

“They thought ‘well we tried it’ and went and got jobs elsewhere, so we saw the disappearance of a lot of big names and there was definitely an era change. I remember sitting there and thinking, yeah, Dad was right.”

Since franchises offered massive, inflated salaries, amateur organisations could not offer the same numbers, and therefore found it hard to attract talent. Those who remained stayed for the love of the game.

“At the time no one was in it for the money anyway,” Aleski said. “Everyone in the teams I was in either worked full time or studied as well. As the events dried up most of us felt like we should do other things.

“The biggest impact was that the number of events held across the UK dropped significantly and the national qualifiers dried up.”

Birmingham Salvo’s roster returned to Team Dignitas and London Mint’s members split, with HenryG looking to return to 4Kings who had signed a Finnish roster after their team were drafted.

But 4Kings would become another casualty of the financial crash too, as they released their Scandinavian roster and went dormant in October 2008.

The UK’s elite CS talent spent two years playing in the CGS too, meaning that the lower tier teams were stuck playing against each other and did not have the experience of facing some of the world’s top talent.

“It left a vacuum, and stupidly over a six to 12 month period, the whole scene evaporated,” Gumpster said.

ESL tried to do its bit to keep the scene through the ESL Pro Series (EPS).

The first season began in September 2008, where 12 CS:S and Call of Duty 4 teams competed for a combined prize pool of £30,000.

4Kings beat FMToxic in the final to secure their £5,000 winnings, with the enigmatic Daniel ‘RE1EASE’ Mullan becoming a breakout star after impressing for the runners-up.

For the next two and a half years, the EPS acted as the top division of a three-tier system that allowed amateur teams to progress through.

Gumpster explained: “The EPS was a league of the top 16 teams in the UK playing at the top level, and you’d have the ESL Amateur Series (EAS) which was eight fringe teams trying to get involved with the big, big, boys.

“Underneath that, you had the EAS Open division and obviously all of the Enemy Down stuff going on as well, so there was a three tier system, just in the UK alone!”

Season Two began in early 2009 and saw Trackmania and Quake 3 join the original two games, with ritch’s Crack Clan beating RattlesnK’s Dignitas in the final.

Counter-Strike 1.6 was reintroduced in early 2010 for Season Three as a replacement for Call of Duty 4 – HenryG’s Power Gaming won the CS:S split and vVv Agents won the 1.6 side.

Finally, in Season Four, 1.6 was phased back out and H2O.Good Looking Gaming won the final EPS UK event, because as hinted at above, it did not last long. Two and a half years after its inception, the EPS failed to find a sponsor for Season Five and had no choice but to cease operations across all games.

“To be honest, I remember [the EPS] as just another league,” admitted RobuLuS, who competed in the EPS. “Obviously it had bigger prize pools for the time, and the prestige of ESL, but there was nothing revolutionary.”

ESL also tried to bolser the women’s scene by holding an EAS for female-only teams and by launching a dedicated “Female League” in 2010.

Neither of these had representation from the UK, nor did a domestic female team play in the ESWC from 2007 to its final event in 2016, though Terri ‘KiTTy-KaT’ Mulvey and Abigail ‘Abiii’ Glover did make appearances over the years.

The collapse of the EPS would come a little later than the failure of the CGS, but in the wake of the CGS’s closure in 2008, investment in esports looked like a risky investment path.

The scene was crying out for some regulation to ‘save’ it, but it would not find salvation in the UK’s new governing body, the United Kingdom eSports Association (UKeSA).

The Rise and Meteoric Fall of The UKeSA

With the scene fragmented in 2008, The New World Assembly Group tried to pull together a bunch of organisations to form a new UK esports governing body.

Remember, TNWA had previously acquired Enemy Down in 2007, so they had their own portfolio to bring to the table – which included the original version of epic.LAN called CentralanUK.

Late 2008 saw the UKeSA become a reality, with the likes of the BBC, Team Dignitas, EA, Fnatic and many more coming together to make it happen.

The idea was that the new group could build a sustainable structure for amateur and professional esports in collaboration with the wider community and government. The UKeSA eventually wanted to represent the UK in the now-Saudi Arabia backed International Esports Federation.

They held tournaments too, trying to recreate that three-tier system by announcing a Championship, Premiership and Open Division for UK CS teams to compete in for Season 1.

A tidy £35,000 prize pool to be split across the top two tiers sounded great.

But the UKeSA could not even make their own governing body sustainable, as just one year later in December 2009, they filed for bankruptcy.

“It was supposed to transform UK esports but it fell off the rails quite quickly,” Gumpster said.

The first season of the UKeSA went well, but prize money from that £35,000 pool was never paid out, with Team Dignitas alone allegedly still being owed £11,000.

That Season One final was disastrous too, as in a telling anecdote, ODEE told Esports News UK editor Dom Sacco (working for tech mag PCR at the time) that his Dignitas team had to go across the road to Tesco to buy a Call of Duty disc, before the tournament organisers didn’t have any.

In the Counter-Strike final, only six of the 24 players attending were from the UK.

Prize money not being paid out was especially bad considering that most teams had to pay an entry fee, as Gumpster explained.

“It was the UK version of ESEA, but after Season One and bankruptcy, they didn’t quite tell people that they weren’t going to run Season Two. So people were paying into it, and UKeSA went bust, and the whole scene fell down the hole and everything went completely in the wrong direction.”

Gumpster speaking on distrust from the UKeSA and how everything fell apart

Since the TNWA also owned Enemy Down, they completely reinvented the website in tandem with the launch of the UKeSA.

“They moved it from a .co.uk to a .eu,” Gumpster remembered. “The new website was awful, it didn’t launch well and there were numerous delays to the new features, so Enemy Down got caught in a crossfire.”

Former Enemy Down admin Cornish also saw this as the beginning of the end for the platform.

Cornish defeatedly said: “This was when I started to lose my passion for the site. They tried to take so much on and it just didn’t work at all.”

It was an ill-fated idea that many players imagined would not work.

“The UKeSA was seen as a non-starter at Starbytes,” MGz said. “Those teams [involved] got invited to events not on merit, but because they were part of some international sort of association.”

With the UKeSA bankrupt, TNWA had some big debts on their hands.

Gumpster said: “It caused further collapse on TNWA, they went bust too, and owed a lot of money.”

With the fall of their parent company, Enemy Down was sold off on December 2nd 2009, right in the wake of the death of the UKeSA.

TNWA’s portfolio also included X-Ray Anti Cheat (XAC) which was a market-leading anti-cheat permanently banning players on community servers on eight different games. It was an anti-cheat trusted by many tournament providers similarly sold off.

“Everything at that point was backed by TNWA, and then it just disappeared across the board,” Gumpster said. “That had a knock on effect where there was no investment, no infrastructure, no nothing. And there was a massive limbo period for the UK scene at that point, which it didn’t quite ever recover from.”

Enemy Down Goes Down

Heaven Media was the conglomerate to save Enemy Down and X-Ray Anti Cheat in December 2009.

The two products joined a portfolio that included Esportsheaven, Crossfire, news site Cadred and Tek9. British esports journalists and personalities Richard Lewis and Thorin gained prominence in CS around this time, reporting for sites like these. You can see an early interview with Richard conducted by Thorin from 2013 here, for insight into their early work.

Back to Enemy Down, and the new owners wanted to quickly change the way the site worked. But the repetition of former mistakes brought about Enemy Down’s eventual death.

Long-standing admin Cornish said: “I stood down from ED when Heaven Media took over because they had very different plans. They wanted to expand it onto Xbox, bringing FIFA leagues and all sorts of stuff, and it wasn’t specifically tailored to Counter-Strike like it had been for most of its life. They tried to take on too much, and because they pumped so much money in, it was deemed a failure.”

While Enemy Down had started as a passion project, the new paid staff who wanted to expand the platform further did too much too soon.

“It was collateral damage from the whole UKeSA situation,” Gumpster said. “They threw money at it too quickly and really there were a lot of background problems with development that should have been addressed first, there were deadline they’d set themselves that they rushed to, instead of just stepping back and saying ‘we’re not going to launch it yet, it’s not ready,’ they pushed broken products.”

The old enemydown.co.uk site ran alongside the new .eu platform, but the old domain quickly became a ghost town.

Suddenly the infrastructure that allowed those rising stars to come through the ladder system back in the early 2000s no longer existed.

“It was a nail in the coffin. A lot of people come to epic.LAN now and congregate, and there isn’t really anywhere online to do that anymore.”

Gumpster speaking on how the closure of Enemy Down hurt the UK CS scene

Efforts have been made to bring some structure to the scene, and the UK & Ireland Circuit (UKIC) has done a great job in partnership with Faceit to bring a four-tier division system for semi-professional and amateur teams to play in.

But back then, there were arguments during Enemy Down’s decline that the ladder system had become outdated, as leagues like ESEA (where fixtures were arranged for you and predetermined) had replaced them.

But Cornish believes that there is no longer a place for more casual players to truly realise their potential ability.

“Getting noticed on Faceit takes so much individual grinding,” Cornish argued. “So for the more casual gamer who doesn’t know how good they can get, that doesn’t necessarily want to grind it, they probably wouldn’t realise that they have natural talent unless you had a platform like Enemy Down or Clanbase to get a taste of competitive play and get a hunger for it.

“Enemy Down let you come in and get a team together with your friends, because matchmaking with a five stack now and playing against five randoms is absolutely nothing like playing against other pre-made teams.”

Gumpster agreed, saying: “Esports has moved on, because back then getting top 100 in a ladder was a hell of an achievement. There were loads of big, big communities all congregating on Enemy Down, and that’s where stars came into fruition. Enemy Down was a staple of Source and the UK scene as a whole, and now there’s nowhere for communities to go.”

Heaven Media eventually merged Enemy Down into Cadred, and while the original .co.uk site remained online until mid 2015, all ladders ceased operation mid-July 2013 due to a lack of competitors.

“I remember even after five years of playing CS, back in the early 00s, we thought that the game was already getting older,” Meffus said in reflection. “So after ten years, and Enemy Down dying, we thought it really could be the end of Counter-Strike.”

In truth, Meffus was half-right.

VeryGames Reinvent Counter-Strike

The UK scene never recovered from the collapse of Enemy Down, and the fragmented players were falling way behind teams on mainland Europe who were changing the landscape of the game tactically.

VeryGames reinvented Counter-Strike by introducing the idea of “executes,” using grenades to overwhelm opponents at a time where teams still relied on raw aim and firepower to win matches.

Like Meffus explained earlier at the CGS, the UK were well known for their mechanical ability, and not so good at the tactical side.

The scene over here just could not keep up.

“We had a forgotten couple of years. VeryGames came over to i-Series events and put the stomp to UK teams.”

Gumpster explaining how the UK CS scene could not beat VeryGames

Between 2010 and 2012, VeryGames won five i-Series LANs, winning four consecutively from i43 to i46. They won every single i-Series that they attended, and their attention to detail blew the UK teams away.

“There was one game where VeryGames lost three rounds, only three rounds,” Meffus began to explain. “And one player managed to get three kills in one of those rounds, so after the game Ex6TenZ [Kevin Droolans, VeryGames IGL] went up to the player and said ‘in that round, weren’t you blind?’

“He wasn’t blind, so Ex6TenZ waned a full recount of where the player was when the flash went off, what he saw, why he wasn’t blind. Ex6TenZ was almost mad at the fact that they hadn’t executed that one flashbang right, even though they only lost three rounds in the whole game.

“That’s why VeryGames were so different, they were obsessed, and Ex6TenZ laid down the foundations for everyone else.”

The UK was in no position to try new tactics and break the rules when it barely had a scene to compete in. A toxic atmosphere was falling on the scene too.

“We had this huge 60m population and a big player base, but you would get heavily crticised for the most minute things,” admitted Vexxy. “It’s hard not to let that affect your self esteem.”

And while the ashes of the UK scene were still settling, Valve made an effort to finally unite the Counter-Strike scene through the release of a new game: Counter-Strike Global Offensive.

The UK Falls Behind in Global Offensive

Valve released Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) in August 2012, and while the scene was still tending to its wounds at this point, the LAN culture was still at least alive and kicking.

Epic.LAN had held its first two events in Stoke in 2009 and was now putting together successful parties in Staffordshire – a positive light in the dark limbos of the scene.

So who were the stand-out teams in the early days of CS:GO?

fm!TOXiC, led by current Heretics Valorant coach Neil ‘nEiLZiNHo’ Finlay, made it to the ESWC 2012, where they were very competitive against the likes of VeryGames and n!faculty but were eventually eliminated dead last in their group.

German organisation Mousesports had also acquired an English line-up of previous heroes, consisting of RattlesnK, ritch, Hughsy, RE1EASE and James ‘Mx’ Smale.

These legends would not last long in Global Offensive.

“We all quit. Aside from the short stint from my boys in CS:GO, Hughsy, RattlesnK, Re1ease etc, the UK had no good players that could live up to [international teams].”

ritch speaking on the transition to Global Offensive, in a Reddit comment sent to Esports News UK

Ritch, “outspoken” as ever, unsurprisingly did not hide his feelings towards this next era of Counter-Strike.

“He hates it now,” Meffus explained, “Because he went off the format in Global Offensive and has never come back to the game. Most of us have this bug, I don’t know if there’s something in the way I’m wired, if it’s what I know, what I’m familiar with, but I always find myself revisiting Counter-Strike.”

While these experienced players were retiring, the younger talent was not yet there to replace them, and the scene was sceptical of Global Offensive’s launch anyway.

“The vibe of the scene was that players either couldn’t adapt, or they thought that GO was the death of the game,” Meffus recalled.

“[Players] thought nobody’s going to go over to GO, the game isn’t ready yet. It’s like the kind of thing that’s happening with CS2 now.”

It is very important to note that the launch of CS:GO was sloppy, and the game certainly was not competition-ready when it was released in August 2012.

“A lot of players tried it and thought it was a mess of a game and that was the end of that,” Meffus said. “They chose to quit and it was unfortunate because I think a lot of players were at the time of their lives were they went from teenagers being able to come home from school and spend all of their time on CS, to now suddenly becoming adults.”

Long-time member of the UK scene sm0ak9 reinforced this mentality, saying: “The game was in a terrible state and took a few years to actually be ‘esports ready.’ For a lot of players, it was a ‘here we go again’ after the difficult 1.6 to CS:S transition.

“They were even saying at the time they were unsure about CSGO as a comp game and may explore other games to compete in. Most of them now have families and either don’t come online much or are playing casual games.”

HenryG also retired as a player around this time, returning to the scene as a caster alongside Anders Blume when Gfinity began to hold LANs in 2014.

4Kings also wanted to have a go in CS:GO, after returning from dormancy in 2010. They looked to establish a foot in the door in Global Offensive, swapping out a Norweigen inspired roster for onscreen, pt, wez, a returning Mangiacapra and David ‘deus’ Kinnaird who were signed in April 2013.

Media took notice, particularly because Mangiacapra was back, but also because the roster were practising in a gaming house in Manchester.

The kicker though? The players were paying for this space themselves.

Just four months later, the team were released.

The players claimed that 4Kings were not willing to fund their travel to events, so they left, and the organisation has been dormant in Counter-Strike ever since.

Money was drying up in the scene, and big name organisations like these made it feel as though they were scurrying from a sinking ship.

“Underfunding has always been an issue in UK CS,” sm0ak9 said. “European talent was rarely attracted to [UK] events and the disparity between professional and amateur teams was quite significant. This meant it was more difficult for players to be recognised by international teams.”

There were teams that kept fighting, and those names deserve credit.

Team Infused captain James ‘redSNK’ Littlewood nurtured talent like Somprasert ‘som’ Haddow and Kia ‘Surreal’ Man in the early years.

Infused kept the UK scene above water for a while too, often acting as the sole representation when worldwide teams came to town.

CEX and fm!TOXiC were well-known brands that bolstered the scene. No list of teams can be complete without mentioning Team Endpoint though, who have propped up the scene since 2016.

Players like Surreal and Max ‘MiGHTYMAX’ Heath have made their careers at Endpoint having joined the roster in 2020.

Not only have they funded several rosters since, but their work behind the scenes for the UKIC has allowed the league system to improve their prize pools and grow their presence.

ESL did eventually return to help the UK scene in 2015, as the EPS was finally replaced by the ESL Premiership in 2015 (see a 13-year-old Reece Barrett try to sum up a week of action here!).

It remained the top national division until all ESL domestic championships were discontinued in 2023, and helped fund the UK scene throughout – allowing Endpoint to open another gaming house after being victorious in 2017.

RattlesnK’s Team XENEX won the first Premiership – the Spring 2015 edition – winning one map with a CGS-esque scoreline of 25-23. His old nemesis HenryG commentated on the event.

But Counter-Strike in the UK hit another low the year before at Insomnia 51 in 2014.

With the lack of big-name sponsors, production values for the event dipped, and there was no CS:GO grand final played on stage as Team Infused beat myXMG to win £1,500.

The idea of “UK CS” was becoming a meme – an ecosystem that nobody took seriously worldwide.

RobuLuS said: “UK CS becoming a meme was funny because it had always been really good, and we were probably the best in CS:S and always around in 1.6. We were always right at the top, but in CS:GO a team just couldn’t come up and fill that gap. We just always had that issue of getting the right players in just one right team with the right attitude.”

Yet elsewhere in Global Offensive, business was booming.

On that same weekend, Copenhagen Games was backed by Intel, Ubisoft and Razer, with the female winners earning double what the i51 champions made.

Not only were Scandinavian events – and their teams like NiP and Fnatic – thriving, but Counter-Strike’s developers also started to stamp their signature on the scene.

Valve introduced officially sponsored “majors” in 2013 which would become Counter-Strike’s flagship competitions.

Sweden dominated the early days, with Fnatic and NiP winning four of the first six majors. Brazil had a brief run as SK Gaming won back to back majors in 2016, CIS’ Gambit pulled off a miracle upset in 2017, and Cloud9 became the first American team to win a major with an unstoppable reverse sweep in 2018.

Countries across continents were making their mark, but what about the UK’s representation at Valve sponsored events?

By 2018, five years and 12 majors after the concept was introduced, not even a single UK player had attended.

So where did it all go wrong for UK CS?

With seasoned veterans retiring, the scene continued to try to reform, but teams were chopping and changing too quickly to actually develop.

Gumpster expanded, saying: “The [UK] has always had a chop shop mentality, where we always think the grass is greener or a good team sees a brilliant player and thinks that they’re the missing piece that they’ve always needed.”

Long-time figure in the scene sm0ak9 agreed.

“Brits are very cynical and you can easily feel like you’re wasting your time after one bad result. There is always a fixation on every mistake, and teams could never seem to stay together whether that be because of the constant poaching that would happen or because people were ousted too quickly before the team could grow together.”

“This is exacerbated by the social stigma in the U.K. where you are expected to go to school, get a degree, enter the job market, buy a house, build a family etc, and deviating from the path is discouraged and looked down on.”

The UK scene had seen plenty of top players give up gaming once they had graduated university – RE1EASE and RattlesnK were examples of that.

“I remember RE1EASE specifically saying that he didn’t know what was happening,” Meffus said. “He didn’t know if his teams weren’t able to keep up with the meta, but he knew something wasn’t right, maybe he wasn’t right, maybe he’s just not good anymore and he can’t do it. It was the mindset a lot of the older players felt.”

Even current players feel the same way today.

Mezii said: “You don’t have the guidance from mentors in the scene.

“That’s always tough, because if you look at other scenes, like the Danish scene for example who have got IGL after IGL at every stage of their development, but in the UK it’s a bit different.

“It’s tough to know exactly if you’re doing is the right thing or the wrong thing, and if you don’t know that, it’s very hard to improve.

“I think players need to keep grinding and if the opportunities arise then they can move into an international team.”

Former Dignitas player RobuLuS echoed prior claims that grindy platforms like Faceit have changed the path to the top for the worse, saying: “I think Counter-Strike isn’t really Counter-Strike for 99.9% of people these days.

“Counter-Strike has always been about five versus five with coordinated structure and set teams, and playing games like that really weeded out players who weren’t as good as they thought. You’d have some players who weren’t fraggers at all but they’d do really well in teams because they just understood the game, and I mean it sounds elitist, but solo grinding isn’t as important as being in a team.”

RobuLuS on the difference in people’s ideas of what Counter-Strike is today

Gumpster also believes that the UK lacked that clear top-tier event to give domestic teams bragging rights – a problem that he feels has still not been solved today.

Gumpster said: “If someone was to destroy the Premier League one day, what would football teams have to dream of winning? You want to achieve stuff on an international level, sure, but you always want to lift trophies over your nearest rivals and be the local kings.