Carmac on the history of IEM Katowice: From coal miners to councillors and CRT monitors to sell-out crowds

Dom Sacco, Senior Editor

Last Updated: 10/02/2025

Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by AI).

IEM Katowice content powered by Predator Gaming | Photo copyright: Helena Kristiansson, ESL Faceit Group

Ahead of the Intel Extreme Masters (IEM) Katowice 2025 playoffs in Poland, Michal ‘Carmac’ Blicharz, VP of product development at ESL, spoke to media about the history of the tournament, at the Predator Gaming showcase at IEM Katowice 2025. We gained his permission to publish his talk in full below.

“Hey everyone, I’m Michal. I usually take the credit for the work of the hundreds, if not thousands of people that make this event happen. Trust me, taking credit is more of what I do these days than actual work around the event. People don’t believe me, but it’s completely true.

I come from a sports family. My father was a judo coach here in the region. And before he was a judo coach, he went from a little village in Poland and went to school to become a coal miner, and he was digging the coal in this area. It was a really tough job.

Then he became a judo coach. He taught me what he knew, and I’m now teaching my son, what I know, from my father. Years after he moved out, I kind of moved in here with an amazing esports event. So that’s it’s about me.

Let’s move to the history of Intel Extreme Masters, because it’s interesting. IEM started in 2006 and the first finals were in 2007. It was not that much more impressive than in this [modestly sized media] room to be fair. And this was the very first finals of a tournament that last week a million people watched. And it started off like that.

“We had CRT monitors! They were very, very difficult to carry, we didn’t have that much branding and it didn’t look very glamorous. It looks nothing like esports today, but think about that, it was 18 or 19 years ago. That’s how long that story is.”

Michal ‘Carmac’ Blicharz, ESL

And 18 or 19 years ago, we had more than enough people, more people than we had room to serve them that content. So already then we knew it was a journey of growth, we just had no idea where it would get us.

So we traveled the world with Intel Extreme Masters. I have to give kudos to Intel for believing in us from the beginning, when it was really, really tiny. We would go to a Comic Con, rent out a piece of floor space there, build a stage and stream it. We would go to Cebit and a Gamescom and places like that, and there was always a sideshow of something bigger.

We always thought, ‘what would it look like if we had our own big show?’ So our live audiences grew from, I don’t know, 100, 150 to 500 to even 2,000 in the biggest events back then, but we never went really big until a certain point. And here is where the city of Katowice comes in and here’s where the fact that I’m Polish comes in.

Poland, as it turns out, is not a big enough country that I wouldn’t have the same friends as a councilman from Katowice. So when I was travelling around the world doing Intel Extreme Masters events, there were a lot of people and 95% of them were loonies that would send me messages, ‘hey, what do we do, how can we bring Intel Extreme Masters to X, Y and Z place?’

And I got one such message from a person that turned out to be a councilman from Katowice, genuinely asking, ‘hey, what can we do, how can we get an IEM to this city?’

And I looked him up on Facebook, and it turned out my good friend from where I come from was also his friend, so I’m like, ‘okay, let’s try this guy out, let’s pursue this’.

And six months later, the management of ESL Poland and I were in the Katowice City Hall talking, saying that we want the Spedek Arena for IEM. And what happened later was that next January, it looked like this, so thousands [of people turned up].

Sorry, I get emotional when I talk about thousands of people just queueing up.

There’s a little story. It was January, probably -5 or -6 degrees celsius, very, very cold. We had absolutely no idea how many people would turn up, so we came up with a ticketing system, where it was a little bit similar to American theme parks, where you buy a day ticket and you can take any ride and stand in long queues. Or you can buy a premium ticket and you can skip most of the queues.

So at the first IEM, what we did was you could buy a ticket and you would go in through the fast queue, and if you didn’t have a ticket, you queued up with everybody else and you could come in for free, it was no problem. So what ended up happening, obviously there was no benchmark like this, it was the first time ever.

What ended up happening was one hour before the opening, every single seat in the house was full. And I go out and I look and I go, ‘hey guys, did you see that?’

“And I go outside and there’s probably two or three thousand people still waiting outside to get in. So the impact was absolutely incredible.”

Michal ‘Carmac’ Blicharz, ESL

That was our first event and one of the very first [esports] events in the world in an arena of this size, with esports done at this scale and at this magnitude.

What we’ve done since was take care of this event as if it’s our baby, because for me it is, and try to manage it in a way where the magic and the prestige accumulates over the time. This is just one example of what it is. These are the steps that lead all the way to the stage in the arena.

And on those steps we have put the names of all the teams that have lifted the trophies of the Intel Extreme Masters, so that every player that goes to play in front of this crowd, this audience, will read these, will think about that, will ascend to the top of the stage and then come out to the people hopefully with a dream to make sure that his or her team name is on the top of the steps next year.

What the players will see every time they ascend the stage. #IEM pic.twitter.com/OIJBzuygrr

— Michal Blicharz (@mbCARMAC) February 23, 2022

And we do a lot of these things because of something I said a few years ago. [Esports News UK editor Dom Sacco] said hello to me this morning, and reminded me of what I said: ‘Our product is emotion’.

We get emotion out of the crowd if we manage to get emotion out of the players, and we get emotion out of the players if we manage to convince them that this is more than just prize money, it’s it’s about something bigger and deeper.

I’m proud to say that almost every year, one of the winners cries on stage.

And it’s a lot of hard work from a lot of people that have made this event into what it is.

Now, I have no idea where we are in terms of time, so I’ll just keep on talking until they turn off my microphone! (laughter in the audience)

Right, so why does it work? That’s a compulsory chapter in a Predator Gaming type setting.

“Why does it work? Well, because gamers are assholes, basically. What do I mean by that? It’s the type of crowd and it’s been like this for over 10 years, over a decade. It’s the type of crowd that knows very well how to shut themselves off from any kind of marketing. You’re gonna watch Netflix, you’re not gonna see any ads. If you see ads, you’re gonna get pissed off, you’re gonna start ad blocking everything. But to put it short, IEM is the type of thing where you come into the Intel Extreme Masters and the audience simply embraces you.”

Michal ‘Carmac’ Blicharz, ESL

We’ve seen countless times where the community… I’ve sent Reddit threads to some of the sponsors. There was a thread that was totally organic. We had nothing to do with it. It said: ‘Hey, we appreciate the fact that this company supported IEM for so many years. Let’s all say what processors we use from Intel as a thank you.’

We sent it to Intel and it was more powerful than any deck we could have ever sent. Totally organic. Now, why it also works is because this tournament is a showcase of talent, you got the best people, the smartest people with the best hand-eye coordination and communication skills, being able to do incredible things in a video game. What I see their competition as is an expression of talent.

One group of talented people is comparing their talent to another, by means of a video game. And in order to compare someone’s or express your talent to the fullest, you need equipment that doesn’t put any limits on that ability to showcase what you can do.

So just like you’ll have the UEFA Champions League and the football has to be a really good ball and and not something inferior, we need the best equipment, so that the best champions can deliver moments of passion, moments that grip us, moments that make the Earth shake, or at least feel like that inside the Spodek Arena.

And that’s what it’s all about. For us, the emotion isn’t there if the equipment isn’t there, because if the equipment isn’t there, the talent doesn’t show through the right way.

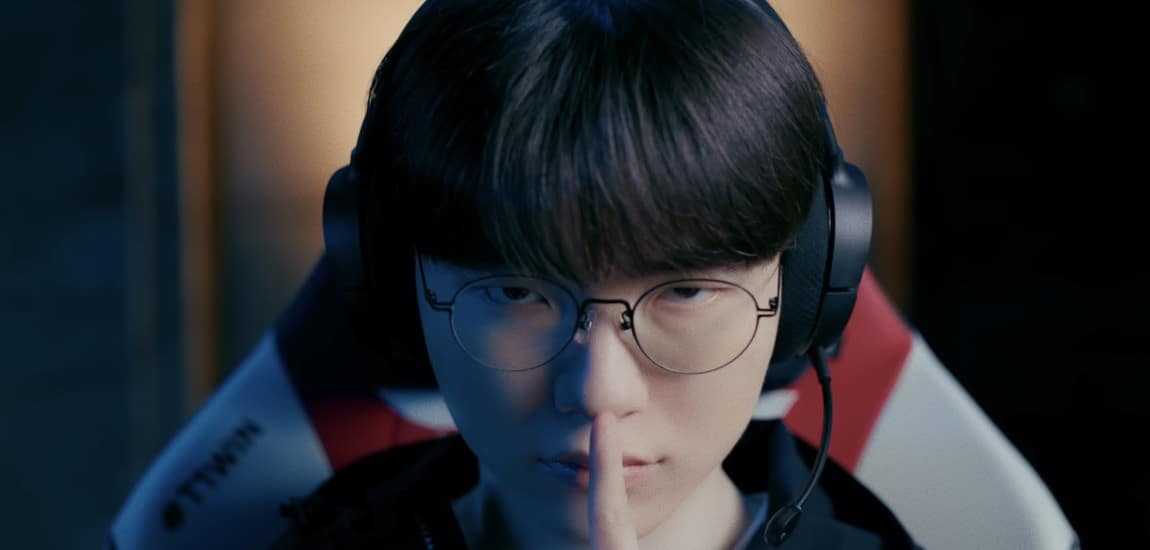

Onto the last slide now. What to look out for this week? So I’ll tell you a little story. The IEM Katowice trophy, the trophy that they’re fighting for, is 18 years old. This guy in the picture, donk, is a few weeks older than the trophy.

That trophy remembers a lot of stories. We put the names of the winners on that trophy. It remembers a lot of new heroes. It didn’t remember a guy like donk last year, until he showed up, and broke practically every record there is in terms of individual performance.

He won the event, lifted the trophy, put his hands in his pockets and went home, made a lot of superstars look very average, and he’s back this year.

So the story of the event is can anybody stop that… can I swear..?

Can anybody stop that monster? They didn’t allow me to swear, sorry.

So, can anybody stop that monster from doing it? And there are people here, there is a Turkish team that are in the playoffs here for the very first time, there’s a Mongolian team in the playoffs here for the very first time. Their coach was here 10 years ago, I think, and continued trying, trying, trying, trying, and they never gave up and they are here in the playoffs.

We have Team Vitality, whose captain, apEX, he’s 31, so quite a bit older than donk. 11 years of coming here. This is his first semi-final.

So it’s going to be a battle of… I’m sorry, this motherf*****! [referring back to donk again]

And those guys will have to win the hard way. So hopefully you enjoy the show, you enjoy some of that story and thank you for having me.

Related article: The emotion of IEM Katowice: 5 of Katowice’s most remarkable Counter-Strike moments

Dom Sacco, Senior Editor

Dom is an award-winning writer and finalist of the Esports Journalist of the Year 2023 award. He has almost two decades of experience in journalism, and left Esports News UK in June 2025. As a long-time gamer having first picked up the NES controller in the late '80s, he has written for a range of publications including GamesTM, Nintendo Official Magazine, industry publication MCV and others. He also previously worked as head of content for the British Esports Federation.

Stay Updated with the Latest News

Get the most important stories delivered straight to your Google News feed — timely and reliable

From breaking news and in-depth match analysis to exclusive interviews and behind-the-scenes content, we bring you the stories that shape the esports scene.

Monthly Visitors

User Satisfaction

Years experience